http://fair.org/extra-online-articles/the-military-industrial-media-complex/

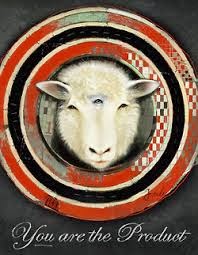

The Military-Industrial-Media Complex

Why war is covered from the warriors’ perspective

By Norman Solomon

After eight years in the White House, Dwight Eisenhower delivered his farewell address on January 17, 1961. The former general warned of “an immense military establishment and a large arms industry.” He added that “we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex.”

One way or another, a military-industrial complex now extends to much of corporate media. In the process, firms with military ties routinely advertise in news outlets. Often, media magnates and people on the boards of large media-related corporations enjoy close links—financial and social—with the military industry and Washington’s foreign-policy establishment.

Sometimes a media-owning corporation is itself a significant weapons merchant. In 1991, when my colleague Martin A. Lee and I looked into the stake that one major media-invested company had in the latest war, what we found was sobering: NBC’s owner General Electric designed, manufactured or supplied parts or maintenance for nearly every major weapon system used by the U.S. during the Gulf War—including the Patriot and Tomahawk Cruise missiles, the Stealth bomber, the B-52 bomber, the AWACS plane, and the NAVSTAR spy satellite system. “In other words,” we wrote in Unreliable Sources, “when correspondents and paid consultants on NBC television praised the performance of U.S. weapons, they were extolling equipment made by GE, the corporation that pays their salaries.”

During just one year, 1989, General Electric had received close to $2 billion in military contracts related to systems that ended up being utilized for the Gulf War. Fifteen years later, the company still had a big stake in military spending. In 2004, when the Pentagon released its list of top military contractors for the latest fiscal year, General Electric ranked eighth with $2.8 billion in contracts (Defense Daily International, 2/13/04).

Given the extent of shared sensibilities and financial synergies within what amounts to a huge military-industrial-media complex, it shouldn’t be surprising that—whether in the prelude to the Gulf War of 1991 or the Iraq invasion of 2003—the U.S.’s biggest media institutions did little to illuminate how Washington and business interests had combined to strengthen and arm Saddam Hussein during many of his worst crimes.

“In the 1980s and afterward, the United States underwrote 24 American corporations so they could sell to Saddam Hussein weapons of mass destruction, which he used against Iran, at that time the prime Middle Eastern enemy of the United States,” Ben Bagdikian wrote in The New Media Monopoly, the 2004 edition of his landmark book on the news business. “Hussein used U.S.-supplied poison gas” against Iranians and Kurds “while the United States looked the other way. This was the same Saddam Hussein who then, as in 2000, was a tyrant subjecting dissenters in his regime to unspeakable tortures and committing genocide against his Kurdish minorities.” In corporate medialand, history could be supremely relevant when it focused on Hussein’s torture and genocide, but the historic assistance he got from the U.S. government and American firms was apt to be off the subject and beside the point.

Spinning civilian deaths

By the time of the 1991 Gulf War, retired colonels, generals and admirals had become mainstays in network TV studios during wartime. Language such as “collateral damage” flowed effortlessly between journalists and military men, who shared perspectives on the occasionally mentioned and even more rarely seen civilians killed by U.S. firepower.

At the outset of the Gulf War, NBC’s Tom Brokaw echoed the White House and a frequent chorus from U.S. journalists by telling viewers (1/16/91): “We must point out again and again that it is Saddam Hussein who put these innocents in harm’s way.” When those innocents got a mention, the U.S. government was often depicted as anxious to avoid hurting them. A couple of days into the war (1/17/91), Ted Koppel told ABC viewers that “great effort is taken, sometimes at great personal cost to American pilots, that civilian targets are not hit.” Two weeks later (1/29/91), Brokaw was offering assurances that “the U.S. has fought this war at arm’s length with long-range missiles, high-tech weapons . . . to keep casualties down.”

With such nifty phrasing, no matter how many civilians might die as a result of American bombardment, the U.S. government—and by implication, its taxpayers—could always deny the slightest responsibility. And a frequent U.S. media message was that Saddam Hussein would use civilian casualties for propaganda purposes, as though that diminished the importance of those deaths. With the Gulf War in its fourth week (2/9/91), Bruce Morton of CBS provided this news analysis: “If Saddam Hussein can turn the world against the effort, convince the world that women and children are the targets of the air campaign, then he will have won a battle, his only one so far.”

In American televisionland, when Iraqi civilians weren’t being discounted or dismissed as Saddam’s propaganda fodder, they were liable to be rendered nonpersons by omission. On the same day that 2,000 bombing runs occurred over Baghdad, anchor Ted Koppel reported (1/23/91): “Aside from the Scud missile that landed in Tel Aviv earlier, it’s been a quiet night in the Middle East.”

News coverage of the Gulf War in U.S. media was sufficiently laudatory to the war-makers in Washington that a former assistant secretary of state, Hodding Carter, remarked (C-SPAN, 2/23/91): “If I were the government, I’d be paying the press for the kind of coverage it is getting right now.” A former media strategy ace for President Reagan put a finer point on the matter. “If you were going to hire a public relations firm to do the media relations for an international event,” said Michael Deaver, “it couldn’t be done any better than this is being done.”

“Through the same lens”

When the media watch group FAIR conducted a survey of network news sources during the Gulf War’s first two weeks, the most frequent repeat analyst was ABC’s Anthony Cordesman. Not surprisingly, the former high-ranking official at the Defense Department and National Security Council gave the war-makers high marks for being trustworthy. “I think the Pentagon is giving it to you absolutely straight,” Cordesman said (Newsday, 1/23/91).

The standard media coverage boosted the war. “Usually missing from the news was analysis from a perspective critical of U.S. policy,” FAIR reported (Extra!, Winter/91). “The media’s rule of thumb seemed to be that to support the war was to be objective, while to be anti-war was to carry a bias.” Eased along by that media rule of thumb was the sanitized language of Pentagonspeak as mediaspeak: “Again and again, the mantra of ‘surgical strikes against military targets’ was repeated by journalists, even though Pentagon briefers acknowledged that they were aiming at civilian roads, bridges and public utilities vital to the survival of the civilian population.”

As the Gulf War came to an end, people watching CBS saw Dan Rather close an interview with the 1st Marine Division commander by shaking his hand and exclaiming (2/27/91): “Again, general, congratulations on a job wonderfully done!”

Chris Hedges covered the Gulf War for the New York Times. More than a decade later, he wrote in a book (War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning): “The notion that the press was used in the war is incorrect. The press wanted to be used. It saw itself as part of the war effort.” Truth-seeking independence was far from the media agenda. “The press was as eager to be of service to the state during the war as most everyone else. Such docility on the part of the press made it easier to do what governments do in wartime, indeed what governments do much of the time, and that is lie.”

Variations in news coverage did not change the overwhelming sameness of outlook: “I boycotted the pool system, but my reports did not puncture the myth or question the grand crusade to free Kuwait. I allowed soldiers to grumble. I shed a little light on the lies spread to make the war look like a coalition, but I did not challenge in any real way the patriotism and jingoism that enthused the crowds back home. We all used the same phrases. We all looked at Iraq through the same lens.”

Legitimating targets

In late April 1999, with the bombing of Yugoslavia in its fifth week, many prominent American journalists gathered at a posh Manhattan hotel for the annual awards dinner of the prestigious Overseas Press Club. They heard a very complimentary speech by Richard Holbrooke, one of the key U.S. diplomats behind recent policies in the Balkans. “The kind of coverage we’re seeing from the New York Times, the Washington Post, NBC, CBS, ABC, CNN and the newsmagazines lately on Kosovo,” he told the assembled media professionals (Palm Beach Post, 5/9/99), “has been extraordinary and exemplary.” Holbrooke had good reasons to praise the nation’s leading journalists. That spring, when the Kosovo crisis exploded into a U.S.-led air war, news organizations functioned more like a fourth branch of government than a Fourth Estate. The pattern was familiar.

Instead of challenging Orwellian techniques, media outlets did much to foist them on the public. Journalists relied on official sources—with non-stop interviews, behind-the-scenes backgrounders, televised briefings and grainy bomb-site videos. Newspeak routinely sanitized NATO’s bombardment of populated areas. Correspondents went through linguistic contortions that preserved favorite fictions of Washington policymakers.

“NATO began its second month of bombing against Yugoslavia today with new strikes against military targets that disrupted civilian electrical and water supplies. . . . ” The first words of the lead article on the New York Times front page the last Sunday in April 1999 (4/25/99) accepted and propagated a remarkable concept, widely promoted by U.S. officials: The bombing disrupted “civilian” electricity and water, yet the targets were “military.” Never mind that such destruction of infrastructure would predictably lead to outbreaks of disease and civilian deaths.

On the newspaper’s op-ed page, columnist Thomas Friedman (4/23/99) made explicit his enthusiasm for destroying civilian necessities: “It should be lights out in Belgrade: Every power grid, water pipe, bridge, road and war-related factory has to be targeted.”

American TV networks didn’t hesitate to show footage of U.S. bombers and missiles in flight—but rarely showed what really happened to people at the receiving end. Echoing Pentagon hype about the wondrous performances of Uncle Sam’s weaponry, U.S. journalists did not often provide unflinching accounts of the results in human terms. Yet reporter Robert Fisk of London’s Independent (4/24/99) managed to do so:

Deep inside the tangle of cement and plastic and

iron, in what had once been the make-up room next to the broadcasting

studio of Serb Television, was all

that was left of a young woman, burnt alive when NATO’s missile exploded

in the radio control room. Within six hours, the [British] Secretary of

State for International Development, Clare Short, declared the place a

“legitimate target.” It wasn’t an argument worth debating with the

wounded—one of them a young technician who could only be extracted from

the hundreds of tons of concrete in which he was encased by amputating

both his legs.

. . . By dusk last night, 10 crushed bodies—two of them

women—had been tugged from beneath the concrete, another man had died in

hospital and 15 other technicians and secretaries still lay buried.

In the spring of 1999, as usual, selected images and skewed facts on

television made it easier for Americans to accept—or even applaud—the

exploding bombs funded by their tax dollars and dropped in their names.

“The citizens of the NATO alliance cannot see the Serbs that their

aircraft have killed,” the Financial Times noted (3/31/99). On American television, the warfare appeared to be wondrous and fairly bloodless.When the New York Times’ Friedman (4/6/99) reflected on the first dozen days of what he called NATO’s “surgical bombing,” he engaged in easy punditry. “Let’s see what 12 weeks of less than surgical bombing does,” he wrote.

Sleek B-2 Stealth bombers and F-117A jets kept appearing in file footage on TV networks. Journalists talked with keen anticipation about Apache AH-64 attack helicopters on the way; military analysts told of the great things such aircraft could do. Reverence for the latest weaponry was acute.

“We got a big thumbs-up”

Mostly, the American television coverage of the Iraq invasion in spring 2003 was akin to scripted “reality TV,” starting with careful screening of participants. CNN was so worried about staying within proper bounds that it cleared on-air talent with the Defense Department, as CNN executive Eason Jordan later acknowledged (CNN, 4/20/03): “I went to the Pentagon myself several times before the war started and met with important people there and said, for instance—‘At CNN, here are the generals we’re thinking of retaining to advise us on the air and off about the war’—and we got a big thumbs-up on all of them. That was important.”

During the war that followed, the “embedding” of about 700 reporters in spring 2003 was hailed as a breakthrough. Those war correspondents stayed close to the troops invading Iraq, and news reports conveyed some vivid frontline visuals along with compelling personal immediacy. But with the context usually confined to the warriors’ frame of reference, a kind of reciprocal bonding quickly set in.

“I’m with the U.S. 7th Cavalry along the northern Kuwaiti border,” said CNN’s embedded Walter Rodgers during a typical report (3/20/03), using the word “we” to refer interchangeably to his network, the U.S. military or both:

We are in what the army calls its attack

position. We have not yet crossed into Iraq at this point. At that

point, we will tell you, when we do, of course, that we will cross the

line of departure. What we are in is essentially a formation, much the

way you would have seen with the U.S. Cavalry in the 19th century

American frontier. The Bradley tanks, the Bradley fighting vehicles are

behind me. Beyond that perimeter, we’ve got dozens more Bradleys and

M1A1 main battle tanks. . . .

Self-imposed constraints

The launch of a war is always accompanied by tremendous media excitement, especially on television. A strong adrenaline rush pervades the coverage. Even formerly reserved journalists tend to embrace the spectacle providing a proud military narrative familiar to Americans, who have seen thousands of movies and TV shows conveying such storylines. War preparations may have proceeded amid public controversy, but White House strategists are keenly aware that a powerful wave of “support our troops” sentiment will kick in for news coverage as soon as the war starts. In media debate, from the outset of war, predictable imbalances boost pro-war sentiment.

This is not a matter of government censorship or even restrictions. Serving as bookends for U.S.-led wars in the 1990s, a pair of studies by FAIR marked the more narrow discourse once the U.S. military went on the attack. Whether the year was ’91 or ’99, whether the country under the U.S. warplanes was Iraq or Yugoslavia, major U.S. media outlets facilitated Washington’s efforts to whip up support for the new war. The constraints on mainstream news organizations were, in customary fashion, largely self-imposed.

During the first two weeks of the Gulf War, voices of domestic opposition were all but excluded from the nightly news programs on TV networks. (The few strong denunciations of the war that made it onto the air were usually from Iraqis.) In total, FAIR found, only 1.5 percent of the sources were identified as American anti-war demonstrators; out of 878 sources cited on the newscasts, just one was a leader of a U.S. peace organization (Extra!, Winter/91).

Eight years later, the pattern was similar: In the spring of 1999, FAIR studied coverage during the first two weeks of the bombing of Yugoslavia and found “a strong imbalance toward supporters of NATO air strikes.” Examining the transcripts of two influential TV programs, ABC’s Nightline and the PBS NewsHour with Jim Lehrer, FAIR documented that only 8 percent of the 291 sources were critics of NATO’s U.S.-led bombing. Forty-five percent of sources were current or former U.S. government and military officials, NATO representatives or NATO troops. On Nightline, the study found, no U.S. sources other than Serbian-Americans were given air time to voice opposition (FAIR study, 5/5/99).

Summarizing FAIR’s research over a 15-year period, sociologist Michael Dolny underscored the news media’s chronic “over-reliance on official sources,” and he also emphasized that “opponents of war are under-represented compared to the percentage of citizens opposed to military conflict.”

“Waving the flag”

Those patterns were on display in 2003 with the Iraq invasion, when FAIR conducted a study of the 1,617 on-camera sources who appeared on the evening newscasts of six U.S. television networks during the three weeks beginning with the start of the war (Extra!, 5-6/03):

Nearly two-thirds of all sources, 64 percent,

were pro-war, while 71 percent of U.S. guests favored the war. Anti-war

voices were 10 percent of all sources, but just 6 percent of non-Iraqi

sources and only 3 percent of U.S. sources. Thus viewers were more than

six times as likely to see a pro-war source as one who was anti-war;

counting only U.S. guests, the ratio increases to 25 to 1.

For the most part, U.S. networks sanitized their war coverage, which was wall-to-wall on cable. As usual, the enthusiasm for war was extreme on Fox News Channel. After a pre-invasion make-over, the fashion was similar for MSNBC. (In a timely manner, that cable network had canceled the nightly Donahue program three weeks before the invasion began. A leaked in-house report

—AllYourTV.com, 2/25/03—said that Phil Donahue’s show would present a “difficult public face for NBC in a time of war. . . . He seems to delight in presenting guests who are anti-war, anti-Bush and skeptical of the administration’s motives.” The danger, quickly averted, was that the show could become “a home for the liberal anti-war agenda at the same time that our competitors are waving the flag at every opportunity.”)

At the other end of the narrow cable-news spectrum, CNN cranked up its own pro-war fervor. Those perspectives deserved to be heard. But on the large TV networks, such voices were so dominant that they amounted to a virtual monopoly in the “marketplace of ideas.”

This article is excerpted from Norman Solomon’s book, War Made Easy: How Presidents and Pundits Keep Spinning Us to Death (John Wiley & Sons, 2005). The first chapter of the book can be found at WarMadeEasy.com.

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen

Da ich kein Toleranz romantiker bin, erlaube ich mir Kommentare ohne Sinn und Verstand zu löschen.